House of Orange-Nassau

Royal Coat of arms of the Netherlands

Country Netherlands

Titles Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Princely Count of Nassau-Dietz, Prince of Orange, Fürst of Nassau-Orange, Fürst of Nassau-Orange-Fulda, Duke of Limburg, Grand Duke of Luxembourg, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, King of the Netherlands

Founder William I of Orange (William the Silent)

Current head Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands

Founding year 1544

Dissolution Since 1962 extinct in the original agnatic line

Ethnicity Dutch

The House of Orange-Nassau (in Dutch: Huis van Oranje-Nassau), a branch of the German House of Nassau, has played a central role in the political life of the Netherlands — and at times in Europe — since William I of Orange (also known as "William the Silent" and "Father of the Fatherland") organized the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule, which after the Eighty Years' War led to an independent Dutch state.

Several members of the house served during this war and after as governor or stadtholder (Dutch stadhouder). However, in 1815, after a long period as a republic, the Netherlands became a monarchy under the House of Orange-Nassau.

The dynasty was established as a result of the marriage of Hendrik III of Nassau-Breda from Germany and Claudia of Châlon-Orange from French Burgundy in 1515. Their son René inherited in 1530 the Principality of Orange from his mother's brother, Philibert of Châlon. As the first Nassau to be Prince of Orange he could use "Orange-Nassau" as his new family name. However, in his will his uncle had stipulated that he should continue the use of the name Châlon-Orange. History knows him therefore as René of Châlon. After the death of René in 1544 his cousin William of Nassau-Dillenburg inherited all his lands. This, William I of Orange, (in English better known as William the Silent) became the founder of the House of Orange-Nassau.

In the late 17th century, the family also supplied a British monarch, King William III who is credited with causing the Glorious Revolution. People around the world still celebrate his battlefield endeavors and the progress in constitutional democracy brought about through his reign, namely in the Bill of Rights 1689, every year in a festival commonly called "The Twelfth".

Contents [hide]

1 The House of Nassau

2 The Dutch rebellion

3 Expansion of dynastic power

4 Exile and resurgence

5 The second stadtholderless era

6 The end of the republic

7 The monarchy (since 1815)

7.1 A new spirit: the United Kingdom of the Netherlands

7.2 William III and the threat of extinction

7.3 A modern monarchy

8 See also

9 External links

[edit] The House of Nassau

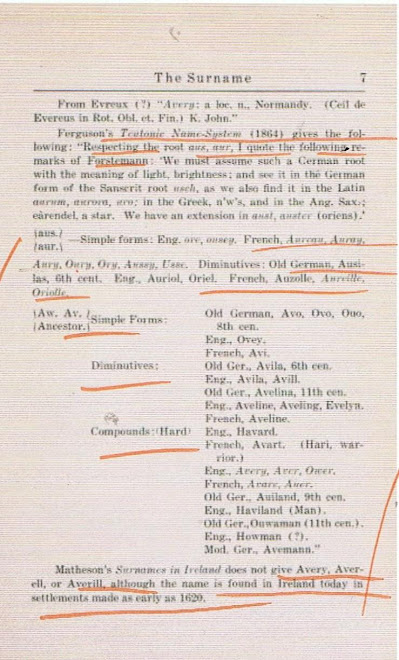

1544 - "Orange-Nassau" symbolized by adding the "Châlon-Orange" arms in an escutcheon to the "Nassau" armsThe first person to be called count of Nassau was Henry I, who lived in the first half of the 13th century. The Nassau family married into the family of the neighbouring Counts of Arnstein (now Kloster Arnstein). His sons Walram and Otto split the Nassau possessions. The descendants of Walram became known as the Walram Line, which became Dukes of Nassau and in 1890 Grand Dukes of Luxembourg. The descendants of Otto became known as the Otton Line, which inherited parts of the Nassau county, properties in France and the Netherlands.

The House of Orange-Nassau stem from the Otton Line. The second person was Engelbert I, who offered his services to the Duke of Burgundy, married a Dutch noblewoman and inherited lands in the Netherlands, with the barony of Breda as the core of the Dutch possessions.

The importance of the Nassaus grew throughout the 15th and 16th century. Hendrik III of Nassau-Breda was appointed stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland by Charles of Ghent in the beginning of the 16th century. Hendrik was succeeded by his son René of Châlon-Orange in 1538, who was, as his full name stated, Prince of Orange. When René died prematurely on the battlefield in 1544 his possessions passed to his nephew, William I of Orange. From then on the family members called themselves "Orange-Nassau."

See also Adolf of Germany

[edit] The Dutch rebellion

Although Charles V resisted the Protestant Reformation, he ruled the Dutch territories wisely with moderation and regard for local customs, and he did not persecute his Protestant subjects on a large scale. His son Philip II inherited his antipathy for the Protestants but not his moderation. Under the reign of Philip, a true persecution of Protestants was initiated and taxes were raised to an outrageous level. Discontent arose and William of Orange (with his vague Lutheran childhood) stood up for the Protestant (mainly Calvinist) inhabitants of the Netherlands. Things went badly after the Eighty Years' War started in 1568, but luck turned to his advantage when Protestant rebels attacking from the North Sea captured Brielle, a coastal town in present-day South Holland in 1572. Many cities in Holland began to support William. During the 1570s he had to defend his core territories in Holland several times, but in the 1580s the inland cities in Holland were secure. William of Orange was considered a threat to Spanish rule in the area and was assassinated in 1584 by a hired killer sent by Philip.

William was succeeded by his second son Maurits, a Protestant who proved an excellent military commander. His abilities as a commander and the lack of strong leadership in Spain after the death of Philip II (1598) gave Maurits excellent opportunities to conquer large parts of the present-day Dutch territory.

Maurits was created stadtholder (military commander) of the Dutch Republic in 1585. In the early years of the 17th century there arose quarrels between stadtholder and oligarchist regents — a group of powerful merchants led by Johan van Oldebarnevelt — because Maurits wanted more powers in the Republic. Maurits won this power struggle by arranging the judicial murder of Oldebarnevelt.

[edit] Expansion of dynastic power

Maurits died unmarried in 1625 and left no legitimate children. He was succeeded by his half-brother Frederick Henry (Dutch: Frederik Hendrik), youngest son of William I. Maurits urged his successor on his deathbed to marry as soon as possible. A few weeks after Maurits's death he married Amalia van Solms-Braunfels. Frederick Henry and Amalia had a son and several daughters. These daughters were married to important houses such as the house of Hohenzollern, but also to the Frisian Nassaus, who were stadtholders in Friesland. His only son William wedded Mary, the eldest daughter of Charles I of England. These dynastic moves were the work of Amalia.

[edit] Exile and resurgence

Painting by Willem van Honthorst (1662), showing four generations of Princes of Orange: William I, Maurice and Frederick Henry, William II, and William III.Frederick Henry died in 1647 and his son succeeded him. As the Treaty of Munster was about to be signed, thereby ending the Eighty Years War, William tried to extend his powers beyond the military to make his function valuable at peace, at the great distress of the regents. When Andries Bicker and Cornelis de Graeff, the great regents of the city of Amsterdam refused some mayors he appointed, he besieged Amsterdam. The siege provoked the wrath of the regents and, unfortunately, William died of smallpox on November 6, 1650, leaving only a posthumous son, William (*November 14, 1650). As there was no Prince of Orange at the death of William II, the regents used the opportunity to leave the stadtholdership vacant. This inaugurated the era in Dutch history, known as the First Stadtholderless Period. The newborn prince was relegated to a disgraceful life. A quarrel about the education of the young prince arose between his mother and his grandmother Amalia (who outlived her husband for 28 years). Amalia wanted an education which was pointed at the resurgence of the House of Orange to power, but Mary wanted a pure English education. The Estates of Holland under Jan de Witt and Cornelis de Graeff meddled in the education and made William a "child of state" educated by the state. The doctrine used in this education was keeping William from rule. William became indeed very docile to the regents and the Estates.

The Dutch Republic was attacked by France and England in 1672. The military function of stadtholder was no longer superfluous and - with support from the Orangists - William was restored, and became stadtholder as William III. William successfully repelled the invasion and seized power. He became more powerful than his predecessors during the Eighty Years War. In 1677 William married Mary Stuart, daughter to future king James II. In 1688 William embarked on a mission to depose his Catholic father-in-law from the English throne. He and his wife were crowned King and Queen of England on April 11, 1689. With the accession to the English throne he became one of the most powerful sovereigns in Europe, the only one to defeat the Sun King. Many members of the House of Orange were devoted admirers of the King-Stadtholder afterwards. He died childless after a riding accident on March 8, 1702, leaving the House of Orange extinct and England to Anne.

[edit] The second stadtholderless era

The regents found that they had suffered under the powerful leadership of William III and declared the stadtholdership vacant for the second time. The main reason was a quarrel about the title Prince of Orange between John William Friso of the Frisian Nassaus and the King of Prussia. Both descended from Frederick Henry. The King of Prussia, Friedrich I was his grandson through his mother, Louise Henriette of Orange-Nassau. Frederick Henry in his will had appointed this line as successor in the case the House would die out. John William Friso was a great-grandson of Frederick Henry and was appointed heir in William III's will. The solution was that both claimants were allowed to bear the title. The problem of the lands solved itself as the principality of Orange was conquered by Louis XIV in 1713. John William Friso drowned in 1711 in the Hollands Diep near Moerdijk and left a posthumous son William IV. He was proclaimed stadtholder of Guelders, Overijssel, Drenthe and Utrecht in 1722. When the French invaded in 1747 William was restored as stadtholder of the whole Dutch Republic, hereditary in both male and female line.

[edit] The end of the republic

William died in 1751, leaving his three-year-old son Willem V as stadtholder. As Willem V was still a minor, the regents ruled for him. Unfortunately, the regents once again deliberately weakened the character of the future ruler, educating him to be indecisive. It would pursue Willem during his whole life. His marriage to Wilhelmina of Prussia relieved this flaw to some degree. Willem's inability to rule properly was a small factor in the collapse of the Dutch Republic, the larger issue being the corrupt regents. In 1787 he survived a coup from the Patriots (democratic revolutionaries) after Prussia intervened. When the French invaded in 1795 he had to flee, and was never to return.

After 1795 the House of Orange-Nassau faced a difficult period, surviving in exile at other European courts, especially those of Prussia and England. Willem V died in 1806.

Dutch Royalty

House of Orange-Nassau

William I

Children

William II

Prince Frederick

Princess Paulina

Marianne, Princess Albert of Prussia

Grandchildren

Louise, Queen of Sweden and Norway

Prince William

Prince Frederick

Marie, Princess of Wied

William II

Children

William III

Prince Alexander

Prince Henry

Prince Ernest Casimir

Sophie, Grand Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

William III

Children

William, Prince of Orange

Prince Maurice

Alexander, Prince of Orange

Wilhelmina

Wilhelmina

Children

Juliana

Juliana

Children

Beatrix

Princess Irene

Princess Margriet

Princess Christina

Beatrix

Children

Willem-Alexander, Prince of Orange

Prince Friso

Prince Constantijn

Grandchildren

Princess Catharina-Amalia

Princess Alexia

Princess Ariane

Countess Luana

Countess Zaria

Countess Eloise

Count Claus-Casimir

Countess Leonore

[edit] The monarchy (since 1815)

[edit] A new spirit: the United Kingdom of the Netherlands

Dutch rebels drove out the French in 1813. It was virtually taken for granted that any new government would have to be headed by William VI, prince of Orange (known in Dutch as Willem Frederik), son of William V. They also figured it would be better in the long term if they restored him themselves[citation needed].

At the invitation of the provisional government, the prince returned to the Netherlands on November 30. This move was strongly supported by the United Kingdom, which sought ways to strengthen the Netherlands and deny future French aggressors easy access to the Low Countries' Channel ports. On December 6, William proclaimed his reign as hereditary sovereign prince (having previously declined the offer of kingship). In 1814 the former Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium) was added to his realm. On March 15, 1815 with the support of the powers gathered at the Congress of Vienna, William proclaimed himself King William I of the Netherlands. He was also made grand duke of Luxembourg. The two countries remained separate despite sharing a common monarch.

As king of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, William tried to establish one common culture. This provoked resistance in the southern parts of the country, which had been culturally separate from the north since 1581. He was considered an enlightened despot.

The Prince of Orange held rights to Nassau lands (Dillenburg, Dietz, Beilstein, Hadamar, Siegen) in central Germany. On the other hand the King of Prussia, Frederick William III--brother-in-law and first cousin of William I had beginning from 1813 managed to establish his rule in Luxembourg, which he regarded as his inheritance from Anne, Duchess of Luxembourg who had died over three centuries earlier. At the Congress of Vienna, the two brothers-in-law agreed to a trade--Frederick William received William I's ancestral lands while William I received Luxembourg. Both got what was geographically nearer to their center of power.

In 1830 Belgium declared its independence and William fought a disastrous war until 1839 when he was forced to settle for peace. With his realm halved, he decided to abdicate in 1840. Royal power was curbed during the reign of his son William II in a constitution ordered by the King to prevent the Revolution of 1848 from spreading to his country.

[edit] William III and the threat of extinction

William II died in 1849. He was succeeded by his son, King William III, a rather conservative, even reactionary man. William III was sharply opposed to the 1848 constitution and constantly tried to form his own royal governments. In 1868, he tried to sell Luxembourg to France, causing a quarrel between Prussia and France.

William III had an unhappy marriage with Sophie of Württemberg and his heirs died young, which began to raise the possibility of the extinction of the House of Orange-Nassau. After the death of Sophie in 1877, William married Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont in 1879. A year later, Queen Emma gave birth to a daughter and heiress, Wilhelmina. Upon Wilhelmina's death in 1962, the House of Orange became extinct in the original agnatic line.

As females weren't allowed to hold power in Luxembourg due to the Salic law, it passed to the House of Nassau-Weilburg, a collateral line. The Dutch Royal Family faced the threat of total extinction until 1909, when Juliana was born. The royal house remained small until the end of the 1930s and the early 1940s, when Juliana's four children were born. Although the royal house died out in the male line with Queen Wilhelmina, the name continues to be used by the Dutch Royal House.

[edit] A modern monarchy

Wilhelmina was queen of the Netherlands for 58 years, from 1890 to 1948. Because she was only 10 years old in 1890, her mother, Queen Emma was regent until her 18th birthday in 1898. She was a symbol of the Dutch resistance during the Second World War. The moral authority of the monarchy was restored because of her rule. After fifty years, she decided to abdicate in favour of Juliana. Juliana made the monarchy less aloof and under her rule the monarchy became known as the "cycling monarchy" as the members of the royal family often cycled through the countryside. A marital policy quarrel occurred in 1966 when future queen Beatrix wanted to marry Claus von Amsberg, a German diplomat. A marriage of a member of the royal family with a German was controversial that may have been exacerbated by Amsberg's former membership in the Hitler Youth and later service in the Wehrmacht. Permission had to be granted from the government for Beatrix to marry him. As time went on, however, Prince Claus became one of the most popular members of the Dutch monarchy and his death in 2002 was widely mourned.

On April 30, 1980 Juliana abdicated in favour of her daughter Beatrix. Beatrix has been somewhat more professional than her mother. At present, the monarchy is popular with a large part of the population. Crown Prince Willem-Alexander was born on 27 April 1967 - the first male heir to the throne in almost 100 years. He married Máxima Zorreguieta in 2002. They have three young daughters: Catharina-Amalia, Alexia and Ariane. When Beatrix dies or abdicates, the Crown Prince will ascend the throne as William IV.

Juliana died on 20 March 2004 and Prince Bernhard, her husband and father of her children, died on 1 December 2004.

[edit] See also

Dutch monarchy

Orange Institution

Order of Orange-Nassau

William III of England

[edit] External links

Dutch Royal House – official website

Iscriviti a:

Commenti sul post (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento